The Greek gods. What if they were alive today? My personal view is that the polytheism of the Greeks gives us a rich language in which to describe experience.

While his sister, Athena, and companion Apollo were focused strategic thinkers, Dionysus was the great loosener. Nothing around him was solid, or stayed the same for very long. His manifold stories cling to him like tendrils of ivy pulled into confusion by the wind.

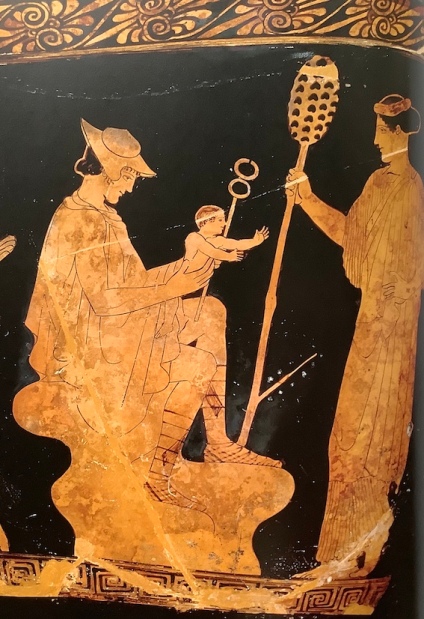

He had three births: first he was born to Zeus and Persephone (Hades’ wife); then (like Egyptian Osiris) he was torn apart by the Titans. Athena saved his heart and Zeus placed it inside Semele, a nymph whom he loved, promising whatever she asked, but when she asked to see him in his full godly physicality his brilliance consumed her with its fire. The baby was pulled from the flames, plunged into a river, then stitched into Zeus’ thigh for a third birth. Forever after he was linked with these two elements: the fiery and the fluid and the symbols he carries on Greek vases are a pine-cone topped staff (the thyrsus as pine is known for its ability to catch light) and a drinking cup.

He was marked by a childhood spent hiding from Hera, queen of heaven, Zeus’ wife, goddess of doing things at the right time in the right way. He had several carers, to whom he was taken by Hermes, or some say Persephone, those two travellers between earth and the underworld, to be hidden in an ivy-clad cave, in a forest, or on a mountain disguised as a girl. Zeus tore off a piece of sky and sent it to Hera as a phantom baby. These mythic links with the other two elements: air and earth, mark him as a figure whose nature flowed through the four elements of air water, fire and earth,

Driven mad by Hera, he wandered round Egypt, Greece, India, dismembering anyone who opposed him, then reconstructing them, or turning them into animals or entwining their minds into shapes of insanity. He loved both men and women, but this gender fluidity intensified rather than diluted his potency. Though he often has a rather languid appearance on Greek vases, to encounter him was like looking into the eyes of a bull.

He and Apollo, whom we think of as disconnected opposites: Apollonian rationalism versus Dionysian ecstatic irrational experience, are in fact a natural pair. Like opposite points on a figure of eight, each is inextricable linked with the other. There’s no need for clarity if there’s no confusion, no relief from constraints without transformation.

His languor derives as much from his connection with wine as his ambiguous gender. Wine is born from the earth and sun, the air and the rain. It is as we know, one of the great looseners. The Greeks sweetened it with honey. We add toxins. They poured libations of wine to the gods, drank it with food from beautifully decorated dishes, with prescribed rituals around its dilution and serving. We might wet a baby’s head, but we go to separate buildings and any rituals are idiosyncratic. Perhaps we should honour that elastic connection between rationality and that other thing. Perhaps we should raise a glass to the spirits of nature as we stand in our lockdown gardens of an evening, or practise friendly distancing on the beach.

Published in Hastings Independent Press July 17 2020